Research OverviewMy research examines interfaces between economy and ecology, culture and nature, value and power. While I have undertaken the bulk of my ethnographic research in the Congo River basin, I have also worked in Southeast Asia and on Africa-Asia engagements. Because I live and work in New York City, some of my newest research looks at ethnographic contexts here at home.

My current research looks at three main topics: relations between people and primates, focusing on the emergence of HIV/AIDS in the forest of southeastern Cameroon; cultural values of elephants, ivory, and global commodity chains that link the Congo River basin with both Asian and Euro-American markets; and cultural values of energy. Each of these projects addresses overlapping conceptual themes: relations between culture and nature, economy and ecology, and value and power. |

|

CONGO RIVER BASIN

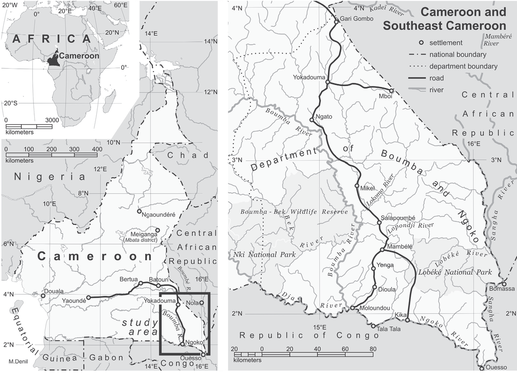

My research is anchored in the Congo River basin, where I have been studying forest communities for the past two decades. As part of a socioeconomic research team working to support the Okapi Wildlife Reserve and the efforts of the Wildlife Conservation Society, I studied economic and ecological contexts of forest communities in the Ituri Forest, in the northeastern region of then Zaire now Democratic Republic of Congo (Rupp 1994). Because of the instability that roiled through the region after the Rwandan genocide in 1994, I changed field sites to the western rim of the Congo River basin. I continued to pursue my interest in the interfaces between culture and nature, economy and ecology, situating my doctoral work in the Lobéké Forest of southeastern Cameroon. I spent twenty-six months conducting ethnographic research among forest communities in the Lobéké Forest region, investigating relationships among four overlapping ethnic groups in order to understand their social, ethnic, and stereotyped identities, and to analyze the ways in which these identities are variably mobilized through policies of conservation, development, missionization, and nationalism. My book-length analysis of these issues was published in 2011, Forests of Belonging: Identities, Ethnicities, and Stereotypes in the Congo River Basin (University of Washington Press). |

Lobéké Forest, Southeastern Cameroon

|

Relations between people and non-human primates

|

Emerging from my research on dynamics of belonging that transcend ethnic categories and bridge categories such as culture and nature, my research includes relations between forest peoples and the animals that share the forest with them. For forest communities in the Congo River basin, boundaries between humanity and animality are substantially more flexible than such categories in Western thought, allowing people to transform themselves into animals and to engage in dynamic social interactions with animals. I have been examining stories of social relations between forest people of the Congo River basin and charismatic species such as great apes (chimpanzees and gorillas). Accounts of such engagements open space for debate among forest people about (in)appropriate engagements between people and animals, and relations between different kinds of people. Narratives of relationships between people and great apes also illustrate the relative porosity of conceptual boundaries between human beings and animals, contributing to social science literature that analyzes evolutionary and social engagement between human and non-human primates. |

|

Historical context of HIV-AIDS emergence in southeastern Cameroon

This research on human-ape boundaries dovetails with current research by two teams of virologists, which have independently identified the Lobéké Forest region of southeastern Cameroon as the location of the chimpanzee community from which the globally pandemic strain of HIV/AIDS originated during the first half of the twentieth century. While there are two strains of HIV (HIV-1 and HIV-2) and several types of each strain, only one type of one strain—HIV-1M, originating in southeastern Cameroon—represents over 95% of all human infections globally (in excess of 30 million infections). Because of my extensive research in precisely this region, in 2011 I joined an international consortium of researchers seeking to analyze the historical, political, and cultural contexts of the first decades of the twentieth century on the rim of the western Congo River basin, the location and time period of the emergence of pandemic HIV/AIDS. We postulate that the human-transmissible virus then spread from southeastern Cameroon along the Congo River and to Kinshasa, the capital of today’s Democratic Republic of Congo, from where the virus made its trans-Atlantic leap to North America (via Haiti). The research team of five historians, one anthropologist (Rupp), one virologist, and one epidemiologist has received a three-year collaborative research grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support this path-breaking research. The larger policy goal of our research is to help anticipate potential contexts for future emerging viruses. Although the Bangando community is small and localized, this group would have been the predominant forest community in contact with colonial officials, markets, and medical posts in southeastern Cameroon, the region where HIV emerged during the first half of the twentieth century. My role in this ongoing collaborative research project is to identify the local changes in the forest environment of southeastern Cameroon—ecological, economic, political, and social shifts in response to burgeoning colonial interest in items such as rubber and ivory as well as meat, skins, and animals—that led to new patterns of hunting, butchering, and marketing of forest products, in particular animals. I am also evaluating ethnographic accounts of medical interventions such as vaccination campaigns, the introduction of surgeries and transfusions, and other colonial medical processes that could have introduced iatrogenic methods of viral emergence. |

AFRICA-ASIA

NEW YORK CITY